The June issue of Psychology Today presents research on creativity that lends weight to two of my recent blog posts, and a number of my closely held beliefs. Which, I’m sure, is their main purpose over there at Psychology Today: looking for solid evidence to shore up my personal theories.

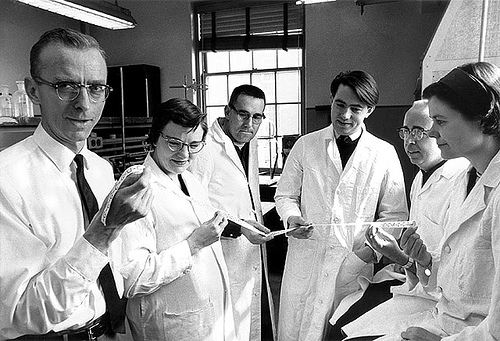

“The Enemies of Invention” explores five “stealth saboteurs” of our creative process in five short articles. It strikes me that Austin Kleon covers similar territory in his book Steal Like An Artist (which I wrote about here) without once mentioning scientific studies. But it’s nice to don our vicarious lab coats once in a while, isn’t it?

“The Enemies of Invention” explores five “stealth saboteurs” of our creative process in five short articles. It strikes me that Austin Kleon covers similar territory in his book Steal Like An Artist (which I wrote about here) without once mentioning scientific studies. But it’s nice to don our vicarious lab coats once in a while, isn’t it?

Christopher J. Sprigman and Kal Raustiala present their version of “Steal Like An Artist” in their piece “The Downside of Avoiding Imitation.” They write:

Very little, if anything, is wrought out of nothing. In practice, creativity is a cumulative process, one that often involves tweaking, adapting, and melding existing creations.

In support of this goal of encouraging a greater migration of ideas, they propose that “too much legal protection” in the form of patent and copyright laws “actually makes it hard to be truly creative.” They argue that shorter periods of protection would lead to more, not less, creative output.

In “Fear of Failure Narrows Vision,” Peter Gray presents research showing that

In physically demanding tasks, like lifting heavy weights, and in tedious tasks, like counting beans, we do better when we are being evaluated than when we are not. But in tasks that require creativity, new insights, or learning, we do better when we are not being evaluated, so are not afraid of failure.

This resonates nicely with the story I quoted in this post from Art and Fear, about the ceramics teacher dividing his class into two groups, and showing that the group being graded by volume of output produced more creative pots than those assigned the making of a single perfect pot.

Gray notes that, from an evolutionary perspective, we can be creative only when we do not feel that our survival is under threat. But being evaluated “when it is not asked for and when it has consequences” causes us to feel threatened. Therefore, being evaluated locks down our creative process.

Gray cites experiments by Harvard Business School psychologist Teresa Amabile in which she had participants create a poem, story or artwork. She told one group their work would be evaluated by experts, another that theirs would be entered into a contest, while a third group was told nothing. Consistently, the most creative work (according to a panel of experts!) was produced by those who did not know they were being evaluated.

Check out the Psychology Today article for three more insightful pieces on creativity crushers and how to avoid them. Then, get out there and make those pots/poems/blog posts. Steal like an artist. Go for quantity.